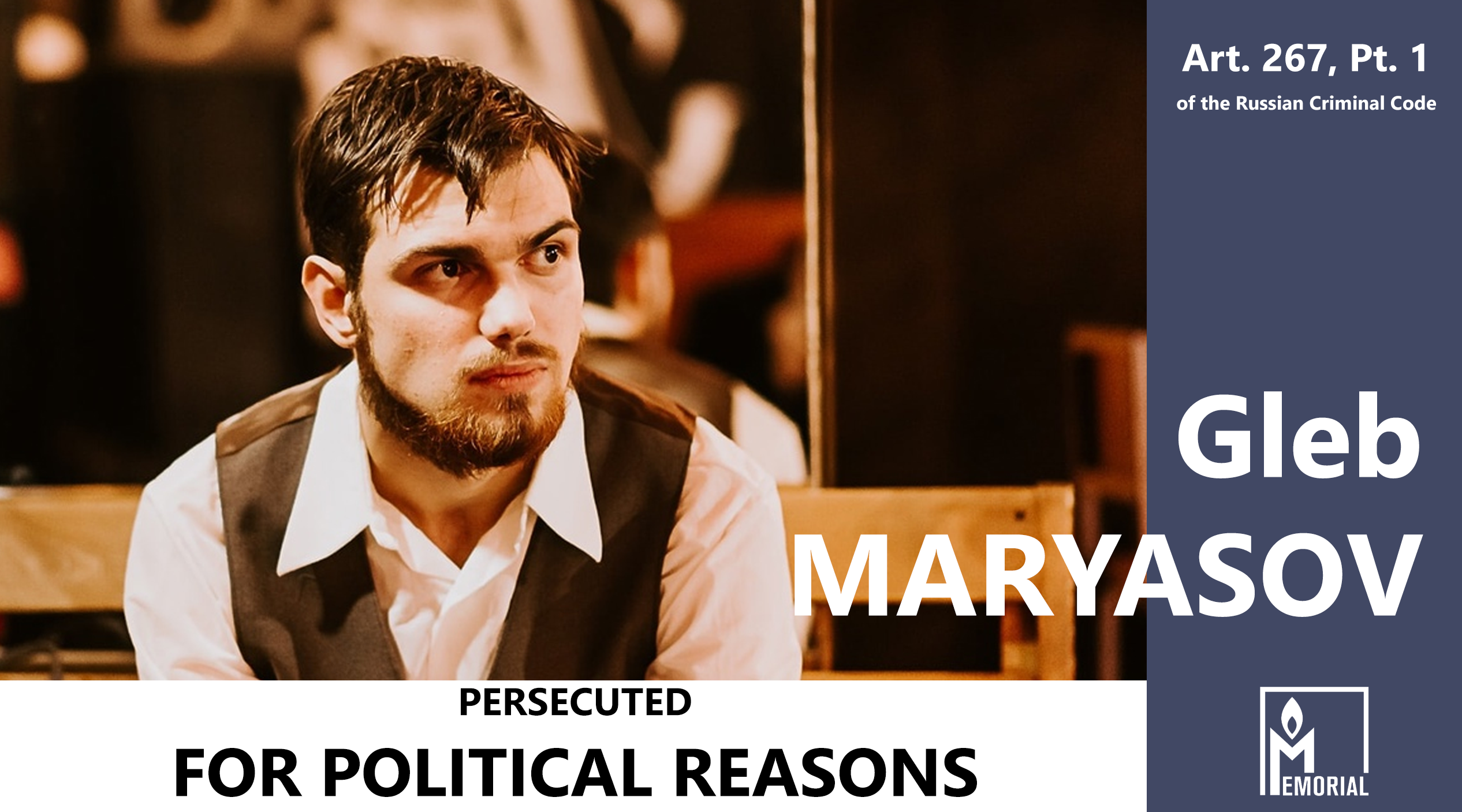

The criminal prosecution of opposition activist Gleb Maryasov is politically motivated and unlawful

Memorial Human Rights Centre, in accordance with international guidelines defining the term ‘political prisoner,’ considers the criminal prosecution of Krasnoyarsk activist Gleb Maryasov politically motivated and unlawful. The purpose of his politically motivated prosecution is to intimidate Russian civil society and prevent citizens exercising their right to freedom of assembly.

We demand that the charges against Gleb Maryasov be dropped immediately and an end to all criminal investigations initiated against peaceful protesters for non-violent actions under the new version of Article 267, Part 1, of the Russian Criminal Code (intentional blocking of transport communications and transport infrastructure or hindering the movement of vehicles and pedestrians on railways and road networks where these acts endanger the life, health or safety of citizens or threaten to destroy or damage the property of individuals or legal entities).

What are the charges against Gleb Maryasov?

On 23 January 2021 protests in support of Aleksei Navalny took place all over Russia. Wherever they occurred, the protests were accompanied by mass arrests and the beating of protesters by the police.

In Moscow, protesters were forced out of Pushkin Square and, seeking to escape from the violence of the security forces, went on to the roadway, thereby obstructing the passage of cars.

It was this circumstance that led on 24 January 2021 to the first criminal prosecution under the newly revised version of Article 267, Part 1, of the Russian Criminal Code that provides for a penalty of up to one year in prison.

The only person charged in the case was Gleb Maryasov, a student at the Siberian Federal University and secretary of the Krasnoyarsk branch of the unregistered Libertarian Party of Russia.

According to the criminal investigators, Maryasov’s crime was that he ‘issued verbal appeals and gave instructions to citizens to move on to the roadway as a united group in the central part of Moscow to block traffic and transport.’

On 22 February the activist was detained as he left a jail where he had been serving a 30-day term for participation in the protests of 23 January.

On 24 February Judge Aleksei Krivoruchko, who has been included in the Magnitsky List, sitting in Moscow’s Tverskoy district court ruled that Maryasov should be banned from undertaking certain specified actions before his trial. In particular, Maryasov was forbidden to return home to Krasnoyarsk and ordered to remain in Moscow at the convenience of the investigators.

Why does Memorial consider Maryasov’s prosecution politically motivated?

- The wording of the new version of Article 267 of the Russian Criminal Code, which criminalizes the blocking of transport communications if such actions ‘endanger the life, health or safety of citizens or threaten to destroy or damage the property of individuals or legal entities,’ hastily adopted in December 2020 along with a number of other unlawful legislative norms, is uncertain in terms of its legal meaning and unjustifiably repressive.

- As a result of the increased severity of Article 267 of the Russian Criminal Code, police officers have in practice been empowered to arbitrarily choose between initiating a prosecution for a criminal offence or for an administrative violation under Article 20. 2, Part 6.1, of the Russian Code of Administrative Offences (participation in an unauthorised assembly, rally, demonstration, march or picket, resulting in interference with the functioning of facilities necessary for life, transport or social infrastructure, communications, the movement of pedestrians or vehicles or access for citizens to residential premises, transport facilities or social infrastructure) solely on the basis of their personal assessment of the degree of danger of this or that delay in the movement of vehicles or, what is even more absurd, pedestrians. Police officers can make this choice solely on the basis of their personal assessment or on the basis of instructions from the anti-extremism police department or the FSB.

- The criminal prosecution is aimed at restricting the freedom of assembly enshrined in Article 31 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation and intimidating participants in protests that do not have official approval. Maryasov has become a victim of a criminal prosecution despite the fact that, on the day of the protest, he not only committed no crime but, on the contrary, behaved exclusively peacefully in situations where he encountered violence from police officers and OMON riot police.

- Most likely, the prosecution of Maryasov, who is a prominent participant in the protest movement, is also related to his oppositionist views. For example, in the autumn of 2020 an activists’ meeting outside Krasnoyarsk, of which Maryasov was one of the organisers, was attacked by unknown assailants and Maryasov’s social media accounts were examined by the anti-extremism police.

A more detailed description of the case and the position of Memorial Human Rights Centre are set out on our website.

Recognition of an individual as a political prisoner, or as a victim of politically motivated prosecution, does not imply Memorial Human Rights Centre agrees with, or approves of, their views, statements, or actions.

You can support all political prisoners by donating to the Fund to Support Political Prisoners of the Union of Solidarity with Political Prisoners via PayPal, using the e-wallet at helppoliticalprisoners@gmail.

Die Lage der politischen Gefangenen und andere Menschenrechtsprobleme verschärfen sich von Jahr zu Jahr. Wir beleben den Dialog zwischen der russischen und der deutschen Menschenrechtsgemeinschaft wieder und bauen ihre konstruktive Interaktion, wechselseitige Information und Unterstützung auf.

Wir stellen Informationen für die deutsche Öffentlichkeit über die Situation des Schutzes von Menschenrechten in Russland und Belarus zur Verfügung und die russische und belarussische Seiten werden entsprechend über den Stand der Dinge auf diesem Gebiet in Deutschland informiert; wir schaffen einen Mechanismus zur Unterstützung russischer und belarussischer Menschenrechtsverteidiger, Opfer politischer Repressionen und politischer Gefangenen.

Wir freuen uns auf Ihre Teilnahme am deutsch-russischen Menschenrechtsdialog auf unserer Website und in den Sozialen Netzen. Ebenso laden wir Sie ein, den Newsletter zu Menschenrechtsfragen zu abonnieren, indem Sie auf den folgenden Link klicken.